When Chami started working as a mahout at the age of 12, about 60 years ago, the captive elephant management scenario in Kerala was very different from what it is today. Back then, he recalls, elephants were symbols of pride and prestige, unlike today, where they are mere money-spinners. There weren’t any Biharis and Assamese, as Chami and other people associated with elephants call the ones from the Sonepur mela and North East. Sixty years later, retired from work, sitting in the verandah of his small home amidst rubber plantations in Parasheri village in Palakkad district of Kerala, Chami’s grief at the plight of captive elephants shows on his face as he speaks. This is not just the view of Chami. His voice represents that of the community of senior mahouts in Kerala. They fear that the new-generation mahouts, who are often mindless, are leading to slow abjection of a centuries-long tradition. A lot of this has become as a result of the change in the way people view elephants. From their status as the living forms of Lord Ganesha, today they’re more revered as celebrities, treated in a manner similar to actors and rock stars, with their own fans associations. This also has made profound influence in the socioeconomics behind the scenes, and I have observed the transformation happening over the past decade and half, from various perspectives. Since there’s a lot more money involved in the business, the art of ‘mahoutry’ as I would put it, has slowly given way to a mere profession aimed at gaining more money. And it was these stark shifts that prompted me to take a short detour from academic days through the land revered for its historical associations and personification with the largest land mammal.

Mahoutry through the ages

Historical records attest that Asian elephants have been kept in captivity as early as the Mauryan Empire (322 to 185 BCE). Since then, elephant capturers and mahouts have sprung from local communities, passing their skills on to further generations. From moods to musth, foot-sores to dysentery, mahouts understood every aspect of elephant management through their traditional practices and long associations with elephants, which made them repositories of knowledge. Matangalila, a millennia old Sanskrit textbook, talk about the biology and management of elephants in captivity besides emphasizing on the ideal characteristics of a mahout. Known for their proficiency in Matangalila, mahouts were once respected for their skills in associating with the largest living land mammal. The opening of the twelfth chapter of Matangalila, written by Nilakantha, classifies the mahouts into three categories as Balavaan (the strong and careless), Rekhavaan (the concerned) and Yukthivaan (the diligent) based on their attitudes and relation with elephants. Most mahouts of yesteryear were well versed with the lore, the practices, and importantly the individual idiosyncrasies of the elephant that was in their charge for years. Years of apprentice to senior mahouts, before becoming an independent mahout themselves, trained them to understand elephant behaviour and care and this was crucial in strengthening the relationship.

Journey from command to chemicals

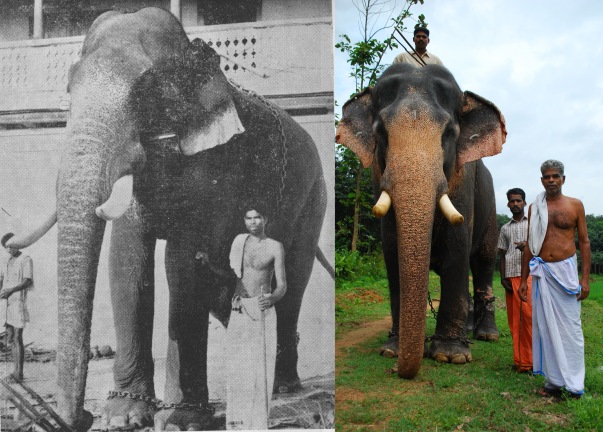

The elephant-mahout relationship used to be a strong bond, an inseparable one, which mostly lasted for decades. (In the order of elephant and mahout names) Koodalattuparam Ramachandran and Gopalan Nair, Mangalamkunnu Ganapathi and Sankaran, Thiruvambadi Kuttisankaran and Narayanan, Thayankavu Manikandan and Gopalan are some of the greatest examples of such relationships. However, in recent years, with changing practices, the tenure of a mahout with an elephant lasts not more than two to three years.

“I learnt the art of being a mahout from my father, and other senior mahouts like Ramachandran Nair”, says Mani, one of the younger mahouts. Mani started working at a very early age, about fifteen years ago, because of his ardent love for the animal. Today things have started changing. Socio-economic and cultural changes have transformed the communities, and the elder mahouts are reluctant to send their wards to this profession considering the wide range of risks that are involved. Considered by most seniors as a promising youngster in the profession, Mani faces opposition from his family, who wants him to quit the job and find better employment in the Middle East. His family is also concerned, that because of the negative perception of the public towards mahouts, they will not be able to find him a bride. Other youngsters are not as interested as Mani is, and many have hardly gained experience as apprentice to senior mahouts, or understood how to handle difficult situations, such as an elephant that goes out of control.

“Tusker runs amok, injures fifty, causes damage to properties”, newspaper headlines like this have been part of the business and this is not new to Kerala’s experience. The 1800s writer Kottarathil Shankunni writes about the heroic tales of yesteryear tuskers and stories of them running amok. But those days, Chami says, mahouts were trained specially to handle violent elephants, and each restraining device, command, and procedure had a purpose and mishaps like human death or injury happened rarely, only in the worst of all cases. In 1979, Kizhakkeveetil Damodaran, a ‘celebrity’ elephant ran amok in a village called Thirunellayi near Palakkad, during a procession terrifying people and damaging property. And that was when it came into the picture, and for the first time in the history of captive elephant management in India, an elephant was brought under control, not by traditional restraints, but chemicals: xylazine hydrochloride fired from a tranquilizer gun. Since then, more than about a thousand incidents of elephants going out of control have been dealt with the help of xylazine. Today 90% of all elephant attack incidents are controlled by the use of tranquilizers. Most cases of elephants running amok happen due to the elephants being in the state of musth, a physiological condition due to increased testosterone levels and characterised by heightened aggressiveness.

Not so pleasant winds of change

On a rainy day in Guruvayur, as he smokes his favorite roll of tobacco, Unnikrishnan, another senior mahout, argues that tranquilizers have been harmful to elephants, in a manner the traditional ankush, a prod of hooked iron, never was. “The ankush may cause external injuries that heal in a while considering the habits of elephants. But the chemical [xylazine] has prolonged effects on musth of elephants and sometimes it even causes burning of skins causing it to tear off [necrosis]”. He adds, “Youngsters support the use of tranquilizers mainly because it is effective in bringing elephant under control immediately, whether you have the mahout’s skill or not”. And when he says this, he’s absolutely right and this attitudinal shift in mahouts have made them less responsible and prompted them to put even musth elephants into work. The numbers of elephants that have died in the past few years or a decade are evidence for the infliction of vicious acts by the young inexperienced lot. Besides ankush, long pole and hobbles these folks now resort to crowbars, sickles and even phosphorous to bring proclaimed rogues under control. Prakash Shankar and Arjun are two young bulls who met a traumatic end in 2009 and 2012 respectively; the former suffered deep wounds on hind legs inflicted by crowbars and the latter had fractured legs caused by a spade!

Such changes in captive elephant management portray dismayingly how the fading of mahout traditions affects the plight of captive elephants. Despite all this, capture is still being suggested as an option to mitigate conflict. Twenty-two elephants were removed from Hassan district in Karnataka, over a period of about six months, earlier last year, as a solution to rising conflict in the area. Experts claim that leaving behind viable populations of elephants, so-called ‘problem elephants’ and ‘rogues’ may be captured to mitigate conflict. But as a matter of fact, capturing/translocating elephants has high chances of leading to more conflict as peripheral herds may move out and colonise the areas from where elephants are captured. But before all that, one needs to defend what defines viable populations and ‘rogues’, although all those are completely different debate. Despite that, capture is being suggested as a viable option to mitigate conflict and recommendations are being made in India for large scale capture of elephants from conflict prone areas. What is overlooked in this case is the fate of these animals in captive conditions, at various forest department or private camps, considering their social status in wild. More challenging is the complexity involved in taming the animals, especially in states like Kerala where mahouts are being more endangered than the elephants. The evanescence of the mahout tradition is evident; there is a great shift from its earlier cultural form to a career people prefer when left with no other option, which has led to reflection of their desperation on elephants in the form of tortures.

As he drives back from the first festival of the season, the Thiruvilwamala Niramala, Aneesh, an elephant enthusiast recollects days during which elephants used to get proper rest, their health ensured. Aneesh who has regularly attended major festivals in Kerala for the last two decades, now restrains himself from attending any. He says, “Many factors have led to tremendous negative changes in the captive elephant sector, a major one being the rise of elephant fan associations that give celebrity status to these poor pachyderms”. He also reminisces how five to seven elephants used to line up for festivals in the past, with hardly any mishaps. In the rare case of an elephant attack, people were usually unaffected, only the mahout being the victim. Deplorably, today many spectators also suffer, such as when the elephant Kalidasan ran amok during the Thrissur Pooram, an annual cultural extravaganza in 2012, or when Thechikottukavu Ramachandran killed three women bystanders at Perumbavoor near Kochi in January 2013. Increasing the number of elephants at each festival has also led to tremendous increase in demand for elephants, as a result of which they are most often overworked, stressed and unhealthy, says Aneesh.

Elephants walking from one festival place to another–a scene from 2000s. Courtesy: Aneesh Sankarankutty

Reports prepared by the Thrissur based Heritage Animal Task Force show that 36 elephants died during the festive season in 2013 and 24 in 2014, most of them under the age of 40, due to overwork and abdominal disorders. These can be clearly attributed to long and strenuous work timings and travel by trucks that are stressful to elephants. Despite several restrictions being in place, including speed limits of the carrying vehicle, they are often violated to ensure timely arrival at a faraway festival place. Most elephants in Kerala are made to stand attendance at about 100-odd festivals every year, traveling roughly 5000 kilometres. In Chami’s prime days as a mahout, he used to walk the elephants for miles from one festival place to another, making stops and availing sufficient rest along the way. As he recalls, those days when three or four elephants used to walk together through the countryside, collecting forage, enjoying toddy pit stops, the elephants rarely knew uneasiness and stress. Today, with vehicles and roads, their travel has become traumatic. Contented of living up to his dreams, training his boys as one of the best set of mahouts in the state, Chami still maintains a ray of hope about the plight of Kerala’s five hundred odd elephants; he’s still hopeful that the winds of change are not far away and that the new generation will soon realise the grave danger they pose to the elephants in the name of celebrityhood and fanatic devotion.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Note: This article was originally published in the Saevus Magazine, September 2015 issue. Reposted by the author on the blog, with additional photographs and hyperlinks.

______________________________________________________________________________________________